If you’re planning a trip to Japan and want to explore beyond the usual cities, why not consider exploring Usuki in Oita prefecture? Whether it’s gorgeous landscapes, Michelin-starred restaurants, old-world traditional architecture, or farm stay experiences you’re after, this part of rural Japan has so much to offer visitors.

Usuki is a far cry from fast-paced city living, but that’s precisely the point: this is a great way to explore the slower-paced side of the country and get a closer look at traditional Japan. Here are just some of the things you can experience in Usuki.

From Uchiko to Usuki

We began our journey in the sleepy but charming little town of Uchiko, nestled in the mountains of Ehime prefecture. The quiet streets in the old quarters are lined with cream-coloured houses in the traditional merchant’s style. Wander along and you’ll find tranquil temples and crafts shops. We loved the stylish but warm hostel-cum-bar Uchiko Bare; there’s a shop a few doors up the street where you can watch the craftsman make Japanese candles in the traditional way––coating wicks with hot wax using his bare hands. If you are lucky enough to stay a night or two at Ori or Hisa––merchant houses converted into breathtakingly luxurious modern villas––all the better.

From Uchiko, we were bound for Usuki, a port town in northern Kyushu located right across the bay. Our two-hour ferry wouldn’t depart until 5 in the afternoon, so a day of sightseeing en route to Yawatahama Port was in order. Ozu, a small town about half an hour’s drive from Uchiko, was the perfect pit stop.

Ozu City

Ozu is a castle town dating back to the Edo period (1603–1867). Like its neighbouring town Uchiko, it enjoyed a brief few decades of prosperity from the end of the Edo period through manufacturing and selling plant-based wax. One of the main attractions is its historic old town. Consisting of several streets and alleyways, a walk through this part of Ozu hints at how life might have been during the Edo and Meiji periods (1868–1912).

Begin your walk at Ohanahan-dori Street. Named for an NHK period drama filmed here, this picturesque old street is lined with rather well-preserved traditional merchant houses and samurai residences. Visitors may take delight, as I did, in the vibrant koi fish swimming in the impossibly clear stream, running along the side of the street.

From here, you might end up wandering to the Ozu Redbrick Hall (Akarenga-kan) that dates back to 1901––now converted to shops and galleries––or Pokopen Yokocho Square, where you can try your hand at old games from the 1950s and 60s. If you’re set on visiting, time your visit well: the stalls here are only open on Sundays between April and November, and then every third Sunday between December and March.

Garyu Sanso

If there is only one place you visit in Ozu, Garyu Sanso should be it. Its name literally means ’Villa of the Sleeping Dragon’! Built in 1907, this is a villa located by the Hijikawa River east of Ozu. It took ten years to design, and a further four years and 9000 artisans to complete its construction. Even today, it’s beloved by Japanese and non-Japanese visitors alike for its highly aesthetic features and design.

The villa is a perfect expression of ‘asobigokoro’ or ‘a playful heart.’ Observe, for instance, the elegant bat-shaped carvings doubling as sliding door handles in the Kagetsu-no-ma (‘foggy moon’) room near the entrance. Here, in an alcove next to a scroll depicting Mt. Fuji, is a circular, latticed cutout in the wall. Why, what should it be but the moon? Sit on the floor facing the alcove and you will see that the shadows cast on the round window seem to showcase the moon in its different phases. You are transported to a moonlit night near Mt. Fuji, with bats flying about––a most charming vision to find oneself in.

Indeed, it is worth devoting some time to enjoy the rich array of visual delights at Garyu Sanso. From the delicate cutouts in the wooden panels, to the magnificent and solid wooden beams above you on the veranda––you don’t get trees like that any more––to the etched stone mills repurposed as stepping stones in the garden, no detail is too small to overlook.

The Furo-an pavilion at the end of the garden is rather ingenious in its construction––we won’t spoil the surprise––but I personally enjoyed the view of the Hijikawa river. On a sunny day, the waters shine bright blue, and it’s impossible not to feel glad just looking at it.

Onwards to Yawatahama Port

After exploring Ozu, it was time to drift onwards to Yawatahama Port.

If you happen to be catching a morning ferry to Usuki, there’s always the option of a seafood breakfast at Yawatahama Port first. Simply head over to the Douya fish market. Zip around and feast your eyes on all the freshly caught fish, before heading over to one of the numerous little stalls outside the market to eat the morning catch. Who wouldn’t want to start their day with fresh sashimi rice bowls and charcoal-grilled shellfish?

Yawatahama Port: Michi no Eki and Citrus Fruits

Those looking for souvenirs would do well to spend some time in the adjacent Michi no Eki. There are the usual tchotchkes from keychains to hair ties, but also squid ink sausages, shelves of instant curry packs sourced from all over the nation, and a tempting array of fresh, local vegetables. (Oh, to have a kitchen on holiday!) But the star here has to be the citrus products.

Ehime prefecture is famous for its staggering variety of domestic citrus, with names like Unshu mikan to Haruka to Shiranui (this last thrillingly written with the characters ‘unknown fire’). You’ll find reasonably-priced, generous bags of locally-grown citrus fruits which make perfect snacks for the ferry ride later.

Most mind-blowing of all must be the walls of citrus juice in-store. Walls. The refrigerator nearest the cashier is lined end-to-end with several different brands of mikan juice. (As with most things in Japan, a higher price often suggests a superior product.) At the back of the store, you’re confronted with another wall of citrus juices beautifully packaged in glass bottles––rather like you’ve stepped into someone’s private wine cellar. (The sign above the shelves roughly translates to “life has all sorts, and there’s all sorts of juices.”) Red Madonna? Jabara? Blood Orange? The hardest part is choosing a bottle to take home.

Yawatahama Port: Crepes are pure heaven

Whatever you end up doing around Yawatahama Port, though, the best thing you can do for yourself is to treat yourself to a crepe from the crepe stand near the market. This unassuming little stall run by a husband-and-wife team turns out some unexpectedly phenomenal crepes. There are enough options on the menu to keep most punters smiling––salted caramel, fruits, and chocolate sauce come to mind–– but you will want to order one of the cream-based combinations. The crepe batter griddles up paper-thin and crispy, and it is trumped only by the impossibly lush cream that’s almost thick enough to stand a spoon in. This is the perfect snack before hopping on a slow boat to Usuki.

Slow Boat to Usuki

Travelling from Yawatahama Port to Usuki is a leisurely, stress-free endeavour. There’s nothing to do but relax on the ferry, and watch daylight fade into starlit night over the ocean waters. Japanese ferries like this typically have a central room where you can nap on the floor––it’s really quite comfortable! It’s a good way to spend a couple of hours as you drift southward.

Alternatively there’s free WiFi on board if you’re easily bored or need to catch up on some work. It’s a little patchy in places, but perfectly serviceable.

Eat Usuki

Kirakuan (Japanese pufferfish/blowfish Kaiseki restaurant)

City is a major destination for fugu lovers, and is home to some 20 restaurants specialising in this deadly delicacy, caught fresh from the ocean waters nearby. Kirakuan, an elegant fugu kaiseki restaurant, is one of the best in Usuki.

Should you worry about eating blowfish? On balance, probably not. Famed for the potentially fatal tetrodotoxin found in parts of the fish, the preparation and sale of fugu at restaurants is strictly controlled in Japan. Fugu chefs must undergo three or more years of training before they can serve the dish to customers. There are some reported instances of poisoning and occasionally fatalities. However, in almost all cases poisoning occurred when the fish was caught and prepared by people at home or when people were served the liver, a practice which is now outlawed.

At Kirakuan, you’ll enjoy a multi-course extravaganza featuring fugu, fugu, and more fugu. Think generous slices of fugu sashimi, delicately flavoured, fresh, and bouncy––a far cry from the flabby stuff in certain big cities. Hunks of fugu, marinated in soy sauce then grilled till lightly oily. Perfectly salted fugu tempura and vegetables alongside.

Just when you think you couldn’t eat more––out comes fugu hotpot, with masses of fish and vegetables cooked in finest Hokkaido kelp stock, making a perfect end to the meal. The hassun seasonal platter that opens the meal deserves a special mention for its exquisitely sticky sesame tofu, simmered black beans, and vinegared sea cucumber.

Name: Kirakuan

Address: 9-kumi, Jonan, Usuki City, Oita 〒875-0041

Website: https://www.kirakuan.jp/

Seigetsuan (Buddhist vegetarian cuisine/shojin-ryori)

Shojin ryori, or Buddhist vegetarian cuisine, tends to receive minimal attention from international visitors compared to sushi or tempura. However, a great shojin ryori meal can be truly life-changing. Visitors to Usuki would do well to book themselves in for lunch at the Michelin-starred Seigetsu-an for a vegetarian culinary experience of a lifetime.

Seigetsu-an’s delightfully whimsical name translates to ‘the place of star and moon.’ The restaurant itself is set in an old Japanese house. Think hanging scrolls in alcoves, elegant seasonal flower arrangements, all manner of interesting paraphernalia lying around, such as wooden chests covered with metal butterfly carvings. And, you don’t have to sit on the floor if you don’t want to––there’s Western-style seating available.

Dishes are slow to emerge, but the wait is worth it. The parade of exquisitely plated dishes begins with the hassun. This seasonal platter typically opens a multi-course meal, and is an assortment of little bites showcasing the best of the season. Everything looks like a painting: moon-like circles of radish encasing dried persimmon; white bean paste moulded into the shape of a camellia flower; simmered ‘clams’ made from gluten. I especially loved the red konnyaku (devil’s tongue jelly), bouncy and gently spicy from a dash of chilli, perfect with a dab of zesty yuzu miso paste.

Dish after dish emerges from the kitchen, each one hitting the high notes of sensory delight. A gorgeously jiggly wodge of sesame tofu; cool, sticky and nutty––possibly one of the best versions of this dish to be found anywhere. A juicy sprig of simmered nanohana (canola blossom) manages to make us all close our eyes in bliss.

Midway, we receive a tiny cup of warm amazake (non-alcoholic rice wine) with a braised strawberry within––perfect for winter. This is followed by an utterly comforting, soupy steamed new seaweed in broth. A Japanese taro ‘shinjo’ dumpling filled with shiitake mushrooms is like eating fluffy potato clouds. With food this delicious, it’s easy to forget that everything is, in fact, vegan.

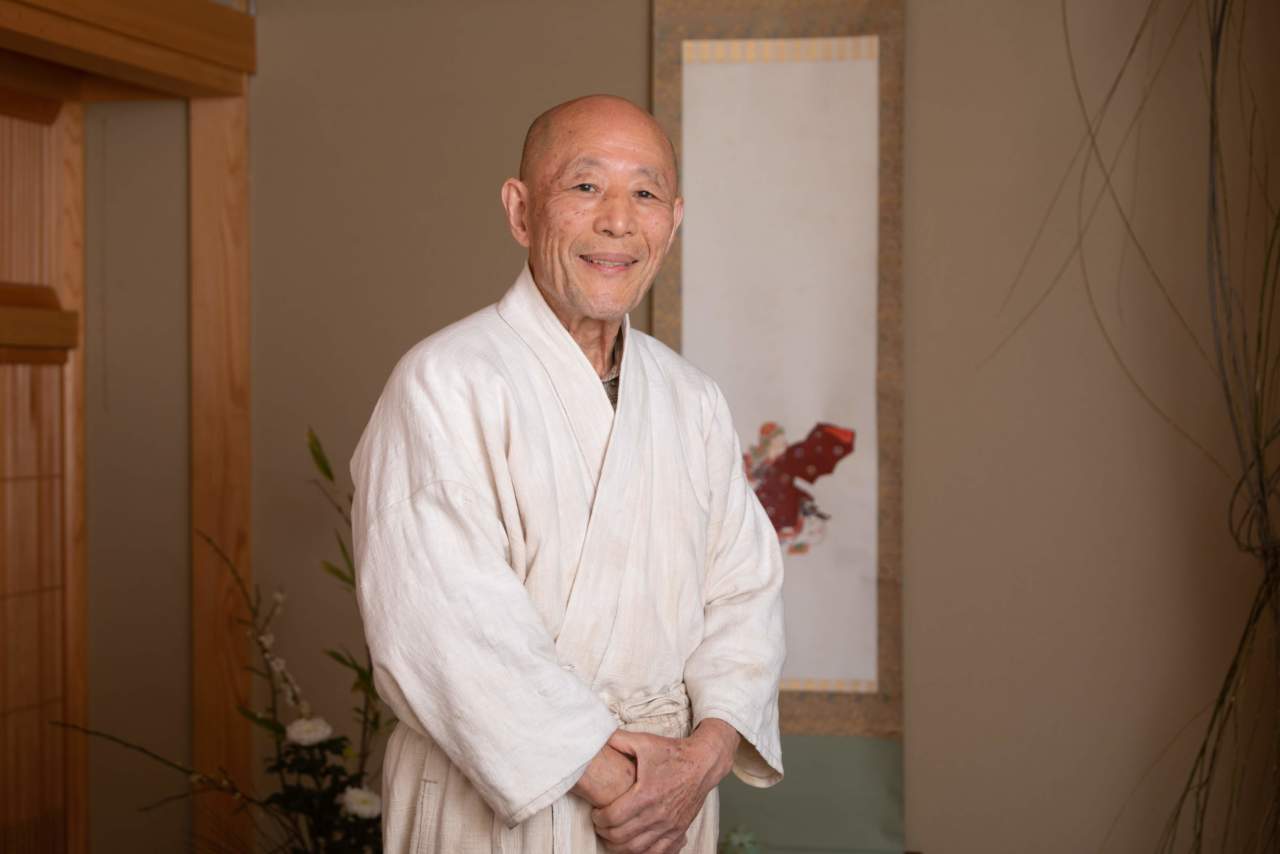

Passion is a prerequisite for anyone running a restaurant, but it shines through in the way head chef Ando Ekun speaks of his craft. Everything sparks ideas: a field of daikon radish was the catalyst for a grilled, grated radish dumpling; beautiful vessels and ceramics inspire new dishes. Food is but a vehicle for his imagination. Of course, it all relies on his exacting technique too. One of the secrets to Seigetsu-an’s cooking is the kelp broth: finest Hokkaido kelp is simmered at a specific temperature for half a day to extract every last bit of flavour.

There are many shojin ryori restaurants around the country, but few can lay claim to official endorsement from the Imperial family’s personal head chef. It’s high praise indeed––Seigetsu-an’s head chef Ando Ekun has much to be proud of with his restaurant in Usuki. It’s reservation-only, so secure your seats before visiting.

Name: Seigetsu-an

Address: 132-2 Kiridori, Nioza, Usuki City, Oita

Website: http://www.kenshouzi.jp/seigetsu/index.html

Sekibutsu Kanko Centre (Local Usuki cuisine)

A visit to the Usuki Stone Buddhas would not be complete without lunch at the Sekibutsu Kanko Centre. Yes, a tourist centre––I was apprehensive, to say the least! Eating at a self-proclaimed tourist centre tends to be a mediocre experience in most places, and I was ready to be disappointed. Thankfully, I love being proven wrong. The food here is simply delicious.

If you try just one thing, go for the signature tachiju, featuring locally caught tachiuo or scabbard fish. Flat fillets of fresh tachiuo are grilled and brushed with a gorgeous soy-based sauce in the style of grilled unagi (freshwater eel). With ribbons of perilla leaf atop and a sprinkle of sansho pepper, the tachiju is a dead ringer for a grilled eel bowl. I might even like it better than most unagi bowls: tachiuo is firm and meaty, and soaks up the sauce beautifully.

Another highlight on the menu is their dangojiru or dumpling soup. They’re not really dumplings, as such––more like thickset wheat noodles. The soup itself is mellow and miso-rich, chock-full of vegetables like radish, carrots, and shiitake mushrooms. Along with the chewy dumplings and some white rice, it makes for an incredibly comforting meal on a cold winter’s day. You might like to have some toriten or tempura chicken alongside, too.

Name: Kyozen Usami (Sekibustu Kanko Centre)

Address: 833-5 Fukata, Usuki, Oita 875-0064

Website: http://sekibutukankocenter.com/

Takahashi Koshindo (Dorayaki––Japanese sweets)

If you happen to join an Usuki-yaki ceramic workshop (see below), you might notice the wooden house next door. It looks a little dilapidated, and it’s easy to dismiss it as another old house in the countryside. But look in the window and you may see an old man in a white apron working at a griddle. This is Takahashi Mutsuo-san, the 74-year old man who runs Takahashi Koshindo with his wife. What you’re witnessing is a lifetime dedicated to dorayaki.

Dorayaki consists of two griddled pancakes sandwiching a generous filling of red bean paste. It’s a common enough snack––you can find it in any convenience store. But your average conbini dorayaki is overly sweet and cloying, stuffed with preservatives, and wildly inferior to one made by a specialist like Takahashi-san. A fresh dorayaki is the stuff of dreams: a warm, soft pancake with all the integrity of good eggs and milk; a red bean paste with just the right amount of sugar, depth and texture. I don’t even like red bean paste, and thought it utterly delicious.

It’s wonderfully hypnotic watching a master pancake craftsman at work. Takahashi-san vigorously whisks the cream-coloured batter before pouring ladlefuls onto a hot iron plate. A minute or so passes, and he flips them by hand to let the other side cook. His timing is impeccable: the cooked sides are a gorgeous, evenly-toasted brown. He tells us that he won’t use any metal implements as they’ll leave visible marks in the pancakes. That’s the mark of a true craftsman, it seems––doing it by hand, even if it burns his fingers.

During our visit, Takahashi-san was kind enough to let us try the freshly griddled pancakes sans red bean filling. I think I like them even better like this––warm and soft, not at all cloying, with a faint sticky sweetness from the honey in the batter. Whisking up a fresh batch of batter right before cooking makes for the best flavour possible. Though there are many shops nationwide that lay claim to dorayaki fame, having tasted Takahashi-san’s creations, my pancake loyalties now lie squarely in Usuki.

Takahashi Koshindo is well-loved by Usuki locals, and they only make 100 dorayaki pancakes a day. Apparently, they rarely take days off. Make sure you get there before they sell out!

Name: Takahashi Koshindo

Address: 大分県臼杵市掻懐8番地

Website: N/A

Osteria Masaki (Italian izakaya/Italian-Japanese gastropub)

Walking around Usuki at night, you’d be forgiven for thinking of it as another sleepy port town––especially on a cold winter’s night, when the streets are empty and silent. But wander down Jokamachi Shopping Street, and all of sudden you’ll encounter life and laughter in the form of Osteria Masaki. This Italian restaurant is like a beacon in the night––warm, welcoming, and perpetually full of customers.

Helmed by Chef Masaki and two helpers, Osteria Masaki is a relative newcomer to Usuki, but is already beloved by locals and out-of-towners alike for its gorgeous food. Expect excellent local ingredients, top-notch cooking, and creative twists on classic dishes. You’ll want to visit with at least one other person so you can sample more dishes on the menu.

It’s worth noting that there are no pretensions of actually being in Italy. Osteria Masaki is more like an Italian-French izakaya (gastropub), and you’ll be eating with chopsticks. It doesn’t feel out of place in the slightest in Japan––if anything, it makes sharing dishes that much easier! Don’t expect a deep dive into a particular region of Italy, either. The menu has pasta and risotto, but also French dishes like pate and steamed mussels.

It would be remiss not to begin dinner with one of their salads. There’s an emphasis on using local, organic Usuki ingredients at Osteria Masaki, and it shows in the dishes. Their salad with carrot dressing is a great example. A winter version saw radish, peppery Indian mustard, rocket, mibuna mustard greens, and lettuce bound together by a vibrant, sweet carrot dressing. Once you’ve tasted fresh, local vegetables, supermarket produce becomes noticeably tasteless by comparison. When was the last time a carrot tasted like a carrot?

Lovers of chicken liver pate are in for a treat. Rich, mellow, and creamy, it’s as good as you’ll get in any French bistro and then some. You’ll want extra slices of bread for the generous amount of pate!

Steamed mussels in white wine are a departure from the usual French bistro version. The mussels are plump and briny, with tender celery leaves and bright hits of acid in the form of tomatoes and lemon. There are few things more comforting for the soul on a cold night than sipping this garlicky broth.

It is quite difficult to go wrong at Osteria Masaki. Try the beef––marbled slices paired with radish and kabu, roasted until sweet and tender and collapsing under your teeth. Or a very respectable dish of pasta Bolognese elevated by sections of roasted leek, sweet and melting within.

The surprise winner at dinner might be the mushroom risotto and foie gras. The risotto is superb; the mushrooms are showcased without being overly dominating and you can hardly complain about a slab of pan-fried foie gras if that’s what you love, but it’s the port wine reduction that makes this dish gloriously memorable. Chopped onions are reduced in plenty of port wine, some balsamic vinegar, and a dash of soy sauce until it transforms into a dark, sweet, savoury glaze. The depth and umami it lends each bite of risotto is unbelievable. You’ll find yourself scraping the plate clean, and wishing you could eat it all over again.

The best part of eating at Osteria Masaki is the fantastic cost-performance, or “cospa” as the Japanese say. The generous portions here would cost twice or thrice as much in Tokyo, and the food is markedly better than many restaurants in the big city––which is testament to how delicious local ingredients are! A meal here is unmissable when travelling through Usuki.

Name: Osteria Masaki

Address: 601 Usuki, Usuki City, Oita

Website: https://www.instagram.com/osteriamasaki/

Travel Usuki

Usuki City

Usuki might seem quiet at first glance, but it has much to offer visitors. You’ll want to spend an afternoon wandering around this former castle town and taking in its offerings. Visit the castle, and follow it with a meander down the shopping street and on to the historic samurai district. The town centre also has a few historic samurai residences open to the public, such as the Inaba Residence and the Marumo Residence.

Exploring on foot is fun, but you might also want to consider borrowing a bicycle from the tourist information centre––for free! If you have enough energy you might even consider cycling all the way to the famous Usuki stone Buddhas instead of taking the bus from town.

Usuki Castle

Whether or not you’re a history buff, no visit to Usuki is complete without a stroll around the castle ruins. The original castle was built on top of Niyuujima, a small island connected to the mainland by a sandbar at low tide. Indeed, Usuki City exists today primarily thanks to land reclamation efforts, with the castle sitting on a plateau in the centre of the city.

The main gate to Usuki Castle is located near the tourist information centre and was rebuilt in 2001. The original bailey (yagura) dating back to the Edo period still remains.

Looking back the way we came, our guide points out the ceramic tiles lining the wall along our path. The curvature of these tiles resembles the spine of a dragon swimming through the sky. Does it mean anything? Probably nothing too deep, but it’s a rather romantic image nonetheless.

On the grounds, there’s a small garden, a replica of the historic ‘country destroyer’ cannon used in the 16th century, a baseball field, and an Inari fox shrine on the grounds. Spring sees the castle grounds awash in a sea of cherry blossoms, making it one of the best hanami (flower-viewing) spots in town.

One of the most intriguing stories about Usuki Castle has to do with the comically-named ‘Unko no Michi’ or ‘Poop Road.’ (You’ll only ever hear this from a local guide!) This refers to one of the back entrances to the castle near the shrine on the grounds.

During the Edo period when faecal matter still had to be manually carried out of the castle––or so the story goes––the castle staff used to sell the daimyo’s excrement to the commoners as they were carrying it out of the aforementioned back entrance. Back then, samurai diets were vastly more nutritious than those of the feudal class, and it was believed that samurai poop made far better fertiliser than that of the common folk.

The practice of buying and selling the daimyo’s faecal matter petered out from the Meiji period onwards––not simply because the feudal system had been dismantled, but also because diets improved so farmers no longer needed to rely on the leavings of the nobility. Nevertheless, the name for the castle’s business end still remains in local lore.

Haccho Oji Shopping Street

The first shopping pit stop for any visitor to Usuki will be Hacchi Oji, a traditional shopping street a short walk away from Usuki Castle and the tourist information centre. Kimono, yukata, Japanese sweets, Usuki’s famous soy sauces, incense, and traditional crafts––the shops here are an eclectic mix of goods. It’s a fun little walk en route to Nioza Historical Street.

One of the highlights on Haccho Oji is Fujiya, one of two local soy sauce shops on the shopping street. Usuki’s soy sauces are fabulous, so picking up a few bottles is a great idea. What you’re here for, however, is their soy sauce soft serve ice cream. It’s infused with katsuojoyu or skipjack bonito-infused soy sauce. Don’t knock till you try it: it’s not salty at all! It’s dense, luscious and buttery, with a faint hint of soy umami that builds slowly as you eat your way through the cone. The soy sauce flavour definitely gets under your skin. Would we order this ice cream again? A thousand times yes. We wish they’d sell this in Tokyo already!

The other soy sauce shop, Kani Shoyu, sells miso soft serve ice cream. It’s equally intriguing and worth trying: a velvety soft serve topped with miso crackers, a caramel-like miso sauce, and a sprinkle of miso powder. What an umami bomb!

Nioza Historical Street

One of Usuki’s main attractions is the Nioza Historical Street. Located parallel to Haccho Oji, it’s a 200 metre-long narrow, sloping street that was part of the old samurai quarters in the city. With its beautifully preserved white stone buildings, wooden temples, and moss-blanketed stone walls, it’s comparable to equally picturesque streets in cities like Dazaifu and Kyoto, but without the hordes of tourists to contend with. Perfect for photo shoots!

It’s also fun to get lost in the little warren of side streets around Nioza. There are quite a few empty houses mixed in with the residences, but there’s plenty in the way of charming details and interesting little finds in this part of Usuki. For instance, you might spot a dozen cabbage heads drying in the winter sun––on the second floor of a balcony below the occupant’s laundry! Or, you might encounter a temple holding matchmaking services for local residents.

Indeed, Usuki has a goodly number of temples to wander into and around, some of which have wonderful wooden carvings and ceramic tiles. One such temple is Zenshoji. The building itself isn’t that old, having been rebuilt in recent years. But you’ll find on the temple grounds near the staircase some fabulous onigawara or demon-face tiles, as well as the ornate fish and dragon tiles used in the previous iteration of the building.

At the top of Nioza Historical Street is Seigetsu-an, the finest shojin ryori (Buddhist temple vegetarian cooking) restaurant in the region. A meal here is unmissable if you’re visiting Usuki. Make your reservations early before your visit.

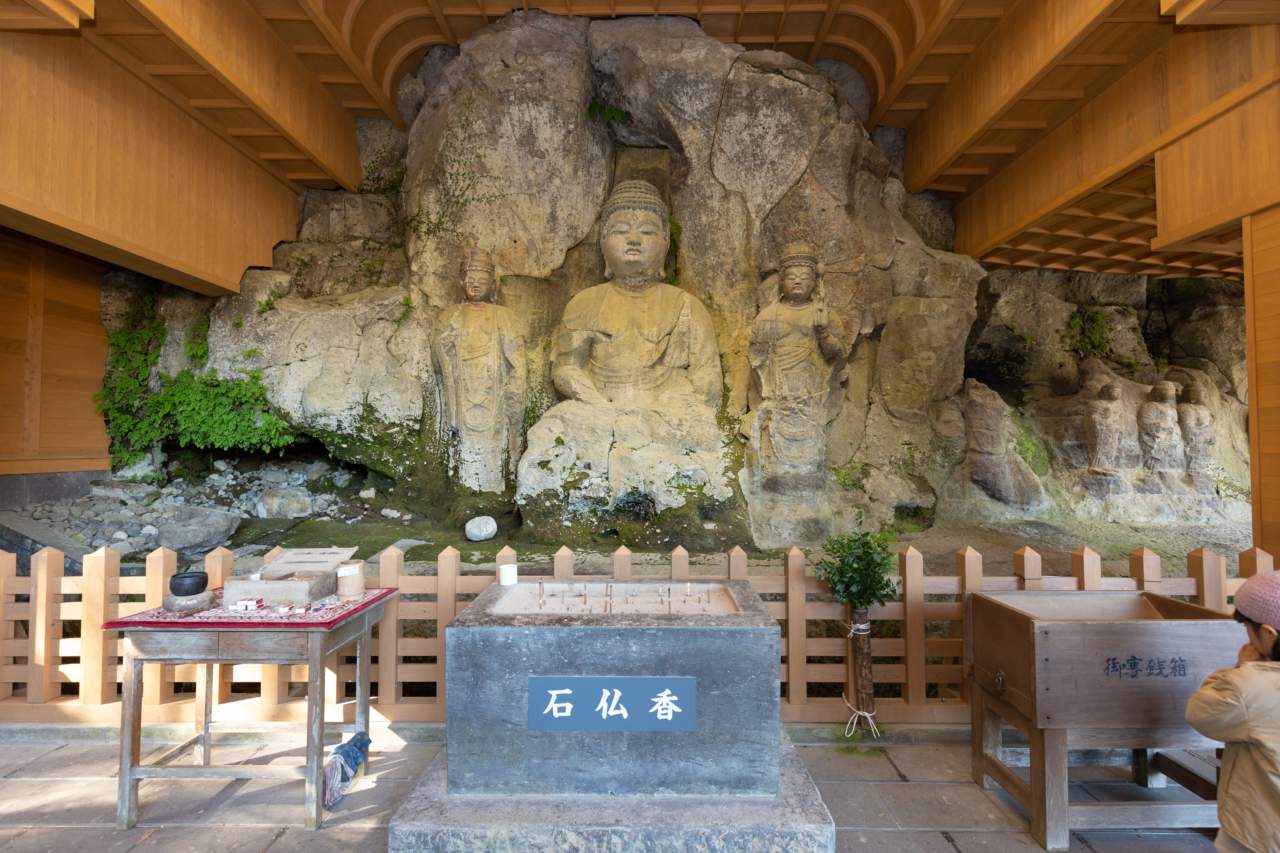

Usuki Stone Buddhas

Buddhist statues aren’t exactly rare in Japan––unless you’re talking about the ones carved directly out of exposed rock, known as magaibutsu. In contrast, most statues you see in Japan are typically wooden or metal three-dimensional. There’s something particularly awe-inspiring, however, about seeing giant carved Buddhist statues emerging from the cliff face.

Some of the most famous stone Buddhas in Japan are in Usuki. In fact, they’re the only ones of their kind to have been designated National Treasures. Dating back to the late Heian period (794–1185), they are carved directly into the soft, volcanic, cliff face, which was the result of Mt. Aso erupting some 90,000 years ago. The soft tuff and lava enabled fine detail work, but also left them susceptible to erosion and necessitated decades of restoration work. These statues would originally have been brightly coloured; the paint work has largely faded with time, but there are still traces of colour that hint at their former awesome appearance.

This area of Usuki once belonged to the Kujo family from Kyoto, the wealthy patrons who funded the construction of these stone Buddhas. While the names of the craftspeople behind the carvings remain unknown, it is thought that they were a group of travelling artisans.

There are four clusters of stone Buddhas, all located a short walk away from each other. There are Buddhas, bodhisattvas, Jizo statues, and Heavenly Kings. Visiting all four clusters takes a leisurely 30-minute stroll. All the statues are pretty remarkable to look at, but the highlight is probably the central carving of Dainichi Nyorai in the Furuzono cluster. Its head had actually lain in front of its body for centuries until it was restored to its rightful position in 1993.

It was said that these statues were a way of learning more about Buddhism and what would happen to you after death. Think of these clusters of carvings as a theme park of sorts––a place for the entertainment and education of locals. Anyone who’s ever visited Singapore’s Har Paw Villa will know exactly what I’m talking about.

Incidentally, the formal enclosures around the stone Buddhas are a relatively recent phenomenon. Ask any of the older locals and they’ll tell you about the good old days when they used to play ball and climb up the statues and play hide and seek here! Now there’s something to imagine.

Experience Usuki

Usuki has much to offer in the way of experiences. These are just a few activities you can try out to make the most of your time in Usuki.

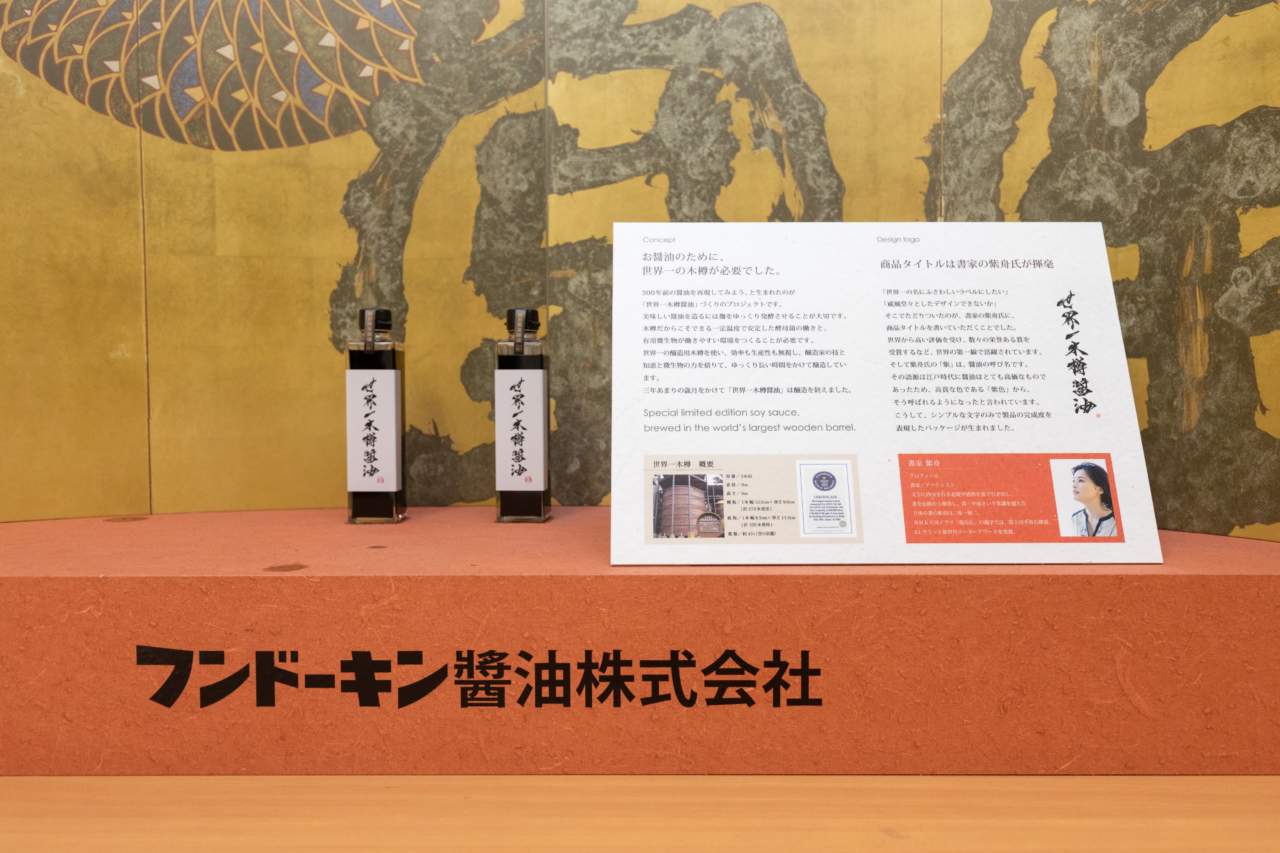

Fundokin Shoyu Factory Visit

Usuki City is home to several soy sauce makers, though there’s just one that offers tours of its facilities––Fundokin.

The history of Fundokin dates back to 1861, when a certain Kotegawa Kanjiro began using the koji-making room in the family’s sake brewery––which was only being used once a year––to manufacture soy sauce and miso paste. While the company began life under another name, it was officially renamed ‘Fundokin’ in 1939. Weathering many storms throughout the war and post-war years, they grew from strength to strength, steadily expanding their manufacturing capabilities.

A quick zip around the factory proves pretty intriguing, even for non-foodies. There are all kinds of delicious scents in the air as you walk around the factory––from the heady fragrance of moromi (fermented soy mash) to the malty smell of koji (aspergillus oryzae; a mould used for making fermented products) to the toasty, nutty scent of roasting wheat. For a condiment that contains so few ingredients––soybeans, salt, wheat, koji, and water–– there are so many variations possible. In fact, Fundokin produces over 800 kinds of soy sauce in its factory!

You get to see most of the soy sauce-making process, from the tanekoji room where they inoculcate steamed white rice with koji fungus, to the machines spitting out tiny soy sauce sachets that go in your supermarket sushi packs. It’s particularly fascinating to see exactly how they extract the soy sauce from the moromi ––litres of liquid drip down through several hundred layers of cloth.

Besides their soy sauce, Fundokin’s other claim to fame is its giant wooden soy sauce barrel––so much so that it received a Guinness World Record in 2002 for this. The barrel measures 9 metres in height and diameter, with walls 9cm thick, and holds around 540,000 litres of soy sauce. We shudder to think what might happen if anyone falls in.

It’s in this barrel that they ferment the moromi for their signature shoyu, whose name roughly translates to “The World’s Best Wooden Barrel Soy Sauce.” They produce just 540,000 bottles every three years. Place your orders early if you want in on one!

Besides the world’s largest barrel, Fundokin also has several other Yoshino cedar wood barrels in which they ferment moromi for about a year. These are the relatively high-quality ones for domestic consumption. The stainless steel barrels, on the other hand, typically contain soy sauce made for export. Being able to regulate temperatures in the stainless steel barrels means that the soy sauces can be ready in as little as 6 months.

If you’re visiting Usuki with time to spare, a visit to Fundokin wouldn’t go amiss. Factory tours are possible when booked in advance. Each group must be accompanied by a Japanese speaker. Please contact Kuratabi Usuki to arrange for a viewing of the facilities.

Name: Fundokin Shoyu Factory

Website: https://www.fundokin.co.jp/

Adachi Farmstay: Making bamboo ware, and coffee with a stupendous morning view

If you’re travelling to Japan, staying at a ryokan might be on your bucket list. But there’s a great alternative to this: spending a night or two on a farm! Not only are you able to meet and spend time with local Japanese people during your travels, you’ll also experience life on a farm, and taste real ‘farm-to-table’ cooking.

A great place for a farmstay in Usuki is at the Adachis. They’re a warm and friendly couple who’ll make you feel right at home. Mr. Adachi is incredibly handy––he created or carved many of the wooden decorations you see around the house, including a low table in the adjacent building!

Their house is located approximately 20 minutes away from the town centre, and overlooks several vegetable fields as well as mountains in the distance. If nothing else, it’s truly special waking up to a view like this at dawn.

Bamboo ware workshop

One of the things you might experience at the Adachi farmstay is a bamboo ware workshop. Here, this is an entry level experience, making bamboo cups and chopsticks––it’s not rocket science, but it’s super fun!

For city slickers like myself, getting to play with an electric sander was such a blast. And, being able to whittle down two rough bamboo rods into slender pointed chopsticks in a matter of minutes feels like magic of some kind.

Picking vegetables

Another fun activity you might be able to experience at the Adachis’ is picking vegetables. No, this isn’t free labour as such––all we’re doing is harvesting what we need for dinner. This being winter, we pulled daikon radish from the ground, and dug up Japanese taro and spicy echalottes. If you visit in spring, you might pick fresh garlic and new onions. Summer brings ripe tomatoes, aubergines, and golden ears of corn.

Dinner with the Adachis

One of the highlights of the Adachi farmstay is, of course, dinner. We eat in the converted storehouse next to their house, seated around the irori (traditional hearth). The space itself is decorated with all kinds of eye-catching miscellanea. There are clothes made from koinobori flags, hand-carved lamps and low tables, a huge embroidered tiger, woodblock prints and paintings, an assortment of gorgeous ceramics. It’s almost like walking into a folk art museum––the Adachis clearly have an eye for items and collectibles.

Mrs. Adachi pulls out all the stops for dinner. We help ferry plates heaped high with food from the kitchen, our mouths watering in anticipation. That night, we feast on deep-fried venison, a gorgeous egg and avocado salad, a chirashi-style rice dish. Just when we think we can’t eat anymore, she brings us more food––eschalot and mugwort tempura, deep-fried fish, steamed egg custard.

But the star of the show must be dangojiru or dumpling stew, a local Oita specialty. Mrs. Adachi makes hers with plenty of fresh root vegetables, leeks, mushrooms, and boar caught by a local hunter (Mr. Oshima of the Wakamizu farmstay below, to be precise!). The fatty boar adds a meaty richness to the soup, which you don’t always find in other renditions of this dish.

A few minutes before serving, she adds the ‘dumplings’ by stretching out supple balls of dough into thick noodles. And right before we eat, she muddles in a ladleful of miso paste––you can’t add it in too early as too much heat will destroy the flavour. The soup is mellow and rich and hearty. It’s perfect for a cold winter’s evening in front of the hearth, and even better when chased with a cup or two of sake.

Breakfast at the Adachis

Faced with this stupendous spread first thing in the morning, I’m reminded of Osaka’s catchphrase: kuidaore, or to eat until you fall over. You couldn’t eat like this every day, but man, is it ever a treat.

Just some of the things in front of us this morning: sunny-side up eggs, sausages, fat tomato wedges, steamed farm-fresh greens. Steamed egg custard chock-full of mushrooms, prawns, mugwort. A plump chunk of fine, spicy cod roe alongside two rice balls. Soft bread from a local bakery, with yuzu jam to go alongside. Coffee jelly with pears and cream. I still dream of that breakfast several weeks later.

Not pictured are the carrots we munched on, tiny orange fingers still with a dusting of soil in the crevices. They taste incredible––sweet and sunny and full of flavour. Indeed, it’s the vegetables at breakfast that leave the deepest impression on me. They taste exactly as they should, a far cry from the perfectly-shaped zombie produce you find in big city supermarkets.

If you’re lucky enough to visit in spring, you’ll enjoy breakfast with a view of their cherry blossom tree from the kitchen. Looking at the mountains over breakfast ain’t too shabby either––it’s a rare treat when you live in the city!

Coffee on the hillside

If the farmstay had ended at breakfast, well, it would have been enough. But if the weather is clement and everyone is willing––and we certainly were––the Adachis will take you to their special place near the house for coffee.

Just a minute or two takes you to a hill overlooking the countryside. Is there anything more blissful than a proper cup of coffee with a view to match? I didn’t think so.

To book a farmstay at the Adachis’, contact KURAtabi Usuki here

Please note that you should bring your own toiletries––while there are some shared amenities and you’ll have a towel, they aren’t a hotel or guesthouse. Don’t expect new toothbrushes.

For the farm-stay and all experiences are required advanced reservation. Please email to kuratabiusuki@gmail.com

Wakamizu Farmstay: Making pickles, cooking with venison, and making deer traps

Staying at a farm is a great alternative to a stint at the more conventional guesthouse or ryokan. Indeed, a stay at Wakamizu, run by the friendly and charismatic Oshimas, is one of the most memorable things you’ll experience in Usuki. Mr. Oshima is famous in the Usuki community for hunting deer and boar, while Mrs. Oshima makes magic in the kitchen.

Even among large farmhouses, the Oshimas’ house is remarkably large and stately. There’s a kitchen outside, and a storeroom with several fridges, each filled with frozen meats, fermented foods, and vegetables. They seem to have the ideal farm existence: they’re close to self-sufficiency, growing vegetables, hunting animals, and even catching fish. Plus, the Oshimas are gregarious and cheerful company––especially Mrs. Oshima––and it’s hard not to feel like you’ve found a second home in the Oita countryside.

While waiting for the activities to commence, we snack on her homemade pickles––daikon radish flavoured with yuzu, rice bran pickles, and salted mustard greens with sesame seeds. The fact that we can’t stop snacking on her pickles is a promise of all the delicious food to come!

Demonstrating Animal Traps

If you’ve ever wanted to know how to hunt, Mr. Oshima is your go-to man. Few others can claim to have been hunting as long as he has––over fifty years and counting in this part of the woods. Having honed his skills and deep knowledge over the years, there’s little that he can’t tell you about hunting deer and boar in the mountains around Usuki.

For instance, he tells us, deer are particularly delicious in the summer––having plenty of grass to eat––but boar are better in winter for having layers of fat on them. (They might be wild boar, but they taste pretty interesting.) You can’t catch boar on flat ground because of their keen sense of smell, so you’ll always have to lay traps at the bottom of slopes.

During our visit, he shows us how he makes his animal traps. It’s difficult to fully describe this metal coil-and-wire contraption in words, but the principle is that the boar or deer steps into the trap, triggering it and causing a metal wire to snap shut around the animal’s leg. It becomes clear the moment he demonstrates how it works––it’s super cool!

Mr. Oshima is well-known in the local Usuki community for his delicious deer and boar meat. The secret? Cleaning and processing the boar or deer right there and then after killing it. Draining its blood within two hours of killing ensures that the meat won’t retain any gaminess that’s so common to boar or venison. Otherwise, the blood stays in the system and muddies the taste of the meat, a principle similar to ikijime for fish. (It makes for much cleaner-tasting sashimi, too.)

While we were unable to experience this for ourselves, Mr. Oshima might take you to the forest and show you exactly how he sets his traps on days with more favourable weather. Keep your fingers crossed for your visit!

Cooking class I: Pickles

Part of the farmstead experience involves making pickles, so Mrs. Oshima shows us how to make a quick kimchi pickle in her wet kitchen space outside. It won’t win prizes for authenticity––it’s no Korean staple––but it’s delicious.

You begin with cabbage, partially dried and lightly salted. But instead of squeezing the salted cabbage by hand to remove all the water, Mrs. Oshima shows us one of her (many) ingenious culinary tricks: all the chopped salted vegetables go into a large laundry bag, and into the washing machine to spin dry. A task that might take the better part of an hour takes just under 10 minutes!

Then, mix in the following with gloved hands: salted kelp, chili peppers, kimchi seasoning, and a small jar of salted prawns. Even freshly made, the kimchi packs a gorgeous tangy umami-filled punch, and it’ll only improve with time.

Cooking class II: Venison

Mrs. Oshima teaches us how to make venison meatballs on our visit. We mince hunks of venison in a food processor, mixing it with breadcrumbs, chopped scallions, salt, pepper, a couple of eggs, milk, oil, amazake (non-alcoholic sweet rice wine), and shiokoji (salted malted rice) to tenderise and add flavour. The secret ingredient here? Two large packets of shredded cheese, which helps keep the meatballs moist and supple. All this has to be kneaded and mixed by hand until elastic and a little shiny. Don’t underestimate how cold the meat mixture gets in winter, especially when the venison has been freshly defrosted.

It’s great fun shaping the meatballs. We take handfuls of the mixture and shape them into palm-sized balls that look like American footballs. (Any smaller and they shrink too much during cooking.) It’s fun when you’re doing it in a group––the work goes much faster too! We leave these to marinate in the fridge.

Later in the evening, Mrs. Oshima simmers them in a rich tomato sauce. In goes tomato juice, quartered tomatoes, ketchup, and a little butter. My mouth is watering just thinking about it.

In the evening, we feast. Mrs. Oshima is an incredible cook. You can almost hear the table groaning under the weight of all the food. We each have a palm-sized deer meatball, a heaped bowl of thick vegetable congee, salad, and all the pickles we can eat.

Best of all, there are thin slices of boar marinated in shiokoji, pan-fried until golden brown at the edges. There’s nary a hint of gaminess in the meat, and it’s utterly moreish dipped in fine pink sea salt.

After dinner, there’s little else to do on a cold night than gather around the warm kotatsu and eat freshly-picked mikan oranges grown by her sister. It’s an utterly blissful way to spend a winter’s evening in the countryside.

Breakfast is yet another ridiculously bountiful spread, this time accompanied by the amusing ups and downs of a Korean period drama playing on the TV in the background. Sipping on my coffee, I’m struck by a sense of nostalgia for the present moment. How is it that I have to leave after just one night? Will I ever taste boar like this again? Will I ever see them again? At least I have her recipe for the venison meatballs. Whether I can hunt a deer using Mr. Oshima’s methods––now there’s another adventure for the future…

To book a farmstay with the Oshimas at Wakamizu, please contact KURAtabi Usuki .

Please note that you should bring your own toiletries––while there are some shared amenities and you’ll have a towel, they aren’t a hotel or guesthouse. Don’t expect new toothbrushes.

For the farm-stay and all experiences are required advanced reservation. Please email to kuratabiusuki@gmail.com

Usuki-yaki: Local Ceramic Traditions

Different regions in Japan are famous for specific, local styles of pottery. You might have heard of more established styles like Arita-yaki in northwestern Kyushu or Kiyomizu-yaki in Kyoto. When you’re in Usuki, the obvious one to check out is local Usuki-yaki!

Usuki-yaki dates back to the later years of the Edo period (1603–1868). The then-lord of Usuki domain summoned four families of potters to Usuki to create Usuki-yaki, and thanks to his patronage, Usuki-yaki flourished for a brief ten years. However, its success was short-lived. This style of pottery went into decline, and eventually ceased to be produced.

In recent years, local ceramic artist Hiroyuki Usami spearheaded efforts to revive Usuki’s ceramic tradition based on surviving pieces, and today produces both porcelain and earthenware in his workshop. Though many of the original Usuki-yaki creations were blue and white porcelain works, he and his colleagues took particular inspiration from a number of flower-shaped works.

These efforts culminated in their signature ‘rinka’ or ‘wheel flower’ series of white porcelain works. Think plates shaped like chrysanthemums, teacups resembling lotus flowers, and chopstick rests in the shape of cherry blossom and chrysanthemums. Indeed, modern Usuki-yaki takes much of its inspiration from natural forms. There is an unassuming grace in each of these pieces.

Many of these contemporary Usuki-yaki works are made from an iron-rich purified tile clay in the Suehiro district. It renders them off-white rather than the stark white colour associated with porcelain, giving them an air of warmth and rusticity. The restrained elegance of Usuki-yaki pieces makes them the perfect vessels for showcasing food.

Make your own Usuki-yaki

Most of us probably don’t give much thought to the plates and cups we use every day––especially when cheap, mass-produced vessels are so easily available. But it really does take commensurate skill to make quality ceramics by hand. A great way to appreciate that is to try making one yourself. What better way to do that than by taking a quick pottery workshop?

At the workshop, you’ll have the opportunity to try making two chopstick rests, one in the shape of a cherry blossom and the other to resemble a chrysanthemum. You begin with a moist ball of clay, which feels fantastic to play with and hold––it’s like being a kid again!

Working with clay is trickier than it looks. Getting it perfectly round looks easy but actually isn’t. But it doesn’t really matter, because it’s all about the experience, not turning out a masterpiece on your first try.

You’ll be directed to pinch and shape the clay and use a long, thin rod to make patterns and petals. Don’t underestimate how satisfying and therapeutic it is!

If you like, they can post your creation to you when it’s baked for an additional fee. Alternatively, you may just want to take one of the professionally produced pieces home!

The Usuki-yaki workshop must be booked in advance. Contact KURAtabi Usuki for more information.

Name: USUKIYAKI Research Center

Website: https://www.usukiyaki.com/

Reservation required for a workshop. Please email to kuratabiusuki@gmail.com

Making incense at Yamamoto Hououdou

If you’ve ever visited a Japanese house, you might have spotted a mysterious-looking, ornately-decorated open cupboard with photos or Buddhist statues inside. These are Buddhist altars, and the majority of Japanese households will typically have one at home. What better place to learn more about Buddhist altars than a shop selling them?

Shinichi Yamamoto is the 5th generation owner of Yamamoto Hououdou, a Buddhist altar shop which has been in operation since 1872. He returned to Usuki at the age of 25 after having travelled around Japan and spent some time apprenticing at another altar-making company.

Though the family trade is in Buddhist altars, he makes a point of telling us that his mother is Christian, and that he spent his childhood attending Sunday mass. Additionally, many of the festivals in Usuki derive from Shinto tradition. This mixed religious upbringing might account for Yamamoto-san’s seemingly laidback nature and approach to life generally.

It’s pretty fascinating learning about the background of Buddhist altars, how they’ve evolved over the years, and the intricacies of the rituals and approaches to religion that they reveal. Yamamoto-san only speaks Japanese, so you’ll need to visit with a translator. It’s worth it if you have a particular interest in this subject though! And even if you don’t have the suitcase space for an altar, he runs incense-making workshops at his shop.

Incense-making workshop

Aromatherapy is a pretty mainstream form of self-care these days. Another way of incorporating that into your life is by burning incense. In a Japanese context, incense smoke purifies your body and spirit, and also acts as a bridge between the spiritual and material realms. You might not have a Buddhist altar in your own home, but there’s no reason you can’t take some incense home to remind you of Japan.

What surprised me most is how easy incense is to make. It’s very similar to mixing cookie dough, and just as therapeutic. You’ll stir a mix of scented powders and colouring pigments together with water––it’s almost like playing in a science lab––and knead it until it becomes a workable dough. I like citrus, so I chose the kabosu-scented powder, but there’s also the option of rose if you prefer a more floral incense.

Then, you roll it out between plastic wrap, and cut shapes out of the incense dough. We’re willing to bet you’ve never seen a cat-shaped piece of incense before!

At the end of the session you’ll have your very own hand-made incense to take home. I plan to fill my apartment with the smell of kabosu and sandalwood to remind me of my days in Usuki!

For a more detailed look into the process, please refer to this link: [https://usuki-tourism.blogspot.com/2019/02/incense-making-experience-at-yamamoto.html]

To book a workshop, contact KURAtabi Usuki . Workshops are conducted in Japanese.

Name: Yamamoto Hououdou 山本鳳凰堂

Address: 3 Tatamiya-machi Usuki-city 大分県臼杵市大字臼杵畳町3

Website: http://hououdou.net/access

Reservation required for a workshop. Please email to kuratabiusuki@gmail.com

From Usuki to Taketa

The most expedient way to get from Usuki to Taketa is by car. While the whole journey won’t take more than an hour or two, it’s fun to take it slow and add a few stops on the way. Try visiting the following places on your travels!

Harajiri Falls

Whoever said not to go chasing waterfalls clearly never visited a place like Harajiri Falls in southern Oita! These falls have been nicknamed the Oriental Niagara––no prizes for guessing why––and are among Japan’s Top 100 Waterfalls. (This country likes their Top 100 lists.) Measuring 20 metres high and 120 metres wide, the falls were formed when Mt. Aso erupted around 90,000 years ago. Walk up close and you can see the columnar joints formed by rapidly cooling lava.

Crossing the suspension bridge gives you the best frontal view of Harajiri Falls. It’s not for those with a fear of heights, so you could trace the perimeter of the falls and back to the car park instead. If you happen to visit during spring, you might be lucky enough to catch the annual tulip festival held in the area.

Don’t forget to stop by the Michi no Eki nearby for a spot of souvenir shopping and a soft serve ice cream. The honey and kabosu soft serve is a favourite with visitors; kabosu is a local citrus tasting like a cross between a lemon, lime, and yuzu. There’s also the “Geo soft,” a geopark-inspired sundae of strawberry and chocolate soft serve with black sesame and chocolate crunchy bits that’s supposed to resemble flowing lava.

Name: Harajiri Falls

Address: 410 Ogatamachi Harajiri, Bungo-ono, Oita 879-6631, Japan

Website: https://www.visit-oita.jp/spots/detail/4544

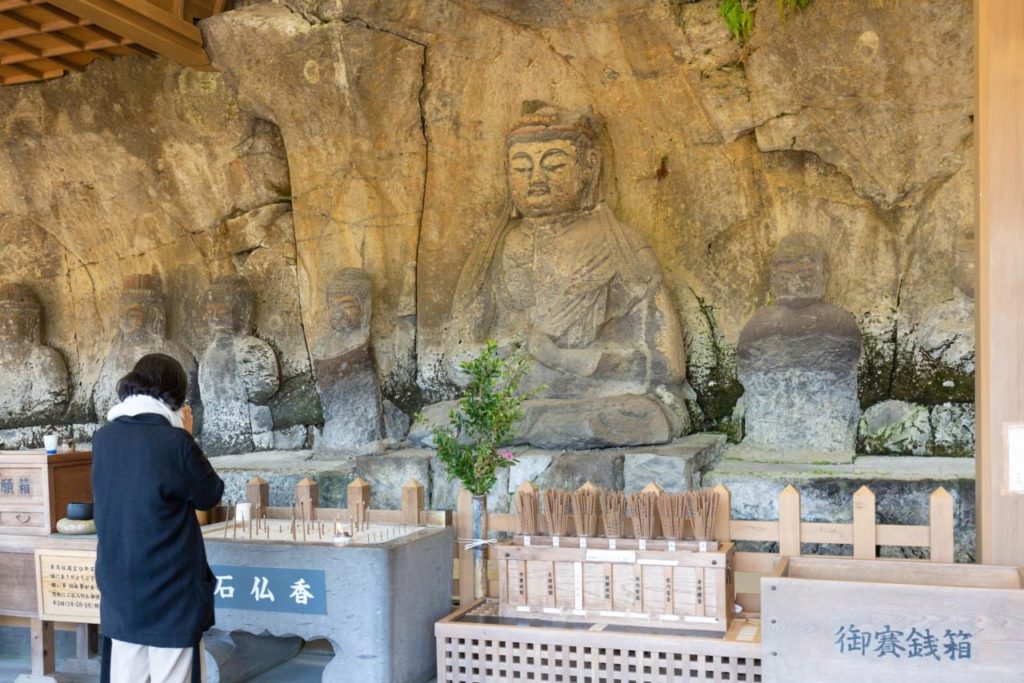

The Stone Buddhas of Fuko-ji

Mt. Aso erupted many times, and the largest eruption happened approximately 90,000 years ago, and its pyroclastic flow created much of the rock formations that still exist today in Oita prefecture. Much of it is soft volcanic tuff––the perfect material for carving magaibutsu. These are Buddhist figures carved directly onto exposed rock, and Oita prefecture has the highest concentration of these stone carvings in Japan. There are quite a few of these sites to visit, but the ones belonging to Fuko-ji Temple in Bungo-Ono must be some of the most impressive around.

To get here, you’ll drive through some utterly beautiful scenery. The temple is sequestered at the end of a country lane in a remote part of Bungo-Ono. While you can visit the temple building, the real draw is the magaibutsu carvings, which purportedly date back to the Kamakura Period (1185–1333). You can’t miss them: three imposing carvings in the cliff right across the valley, of the Buddhist deity Fudo-myoo (The Immovable Wise King) flanked by his attendants Kongara-doji and Seitaka-doji. Exposure to the elements over the centuries has softened their once-fierce expressions.

Besides the three large carvings, there are also two shallow caves in the cliff containing dozens more stone statues. While you can simply look at the statues from afar, we recommend crossing the valley to look at these carvings up close. It shouldn’t take more than a few minutes to walk there, and it is unreal seeing them in person. What I liked most about these magaibutsu is how they’re just there––they really do speak for themselves.

The stone Buddhas of Fuko-ji are only accessible by car––perfect if you’re driving from Usuki to Taketa. Don’t bother trying public transport. You’ll have better luck hitchhiking!

Name: Fuko-ji Temple

Address: Asajimachi Kamiotsuka, Bungoono 879-6213, Oita Prefecture

Website:https://www.discover-oita.com/en/japan-attractions/fuko-ji

A tour of “Usuki” from town to town

Usuki: A Hidden Gem in Kyushu

You can stay in Usuki and go on for a day trip to Beppu!

If you are staying in Usuki, it is manageable to visit Takachiho and return in a day